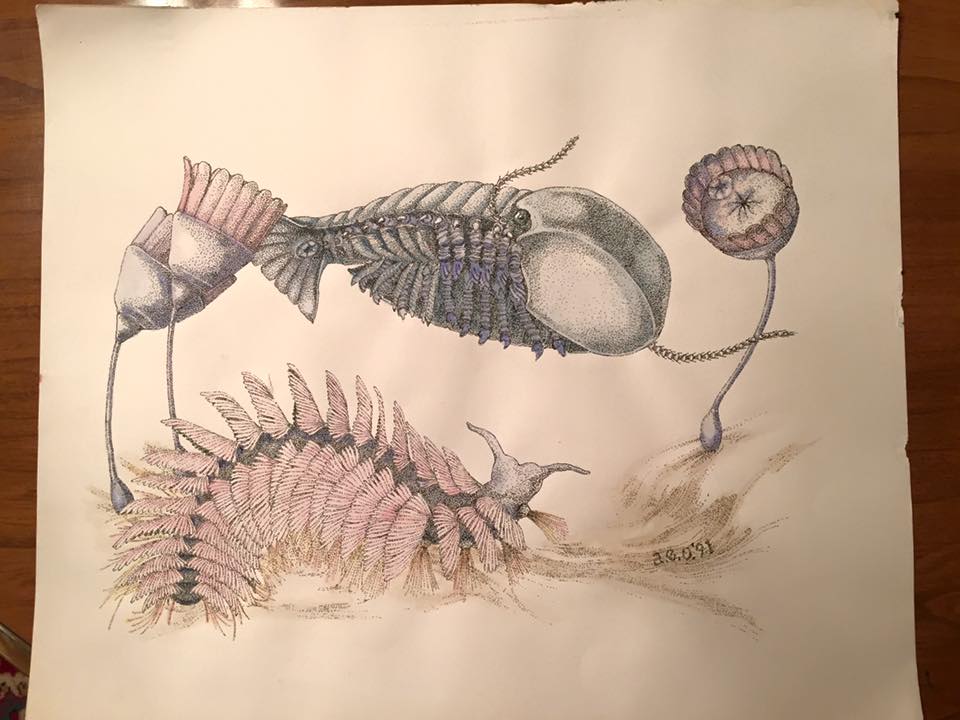

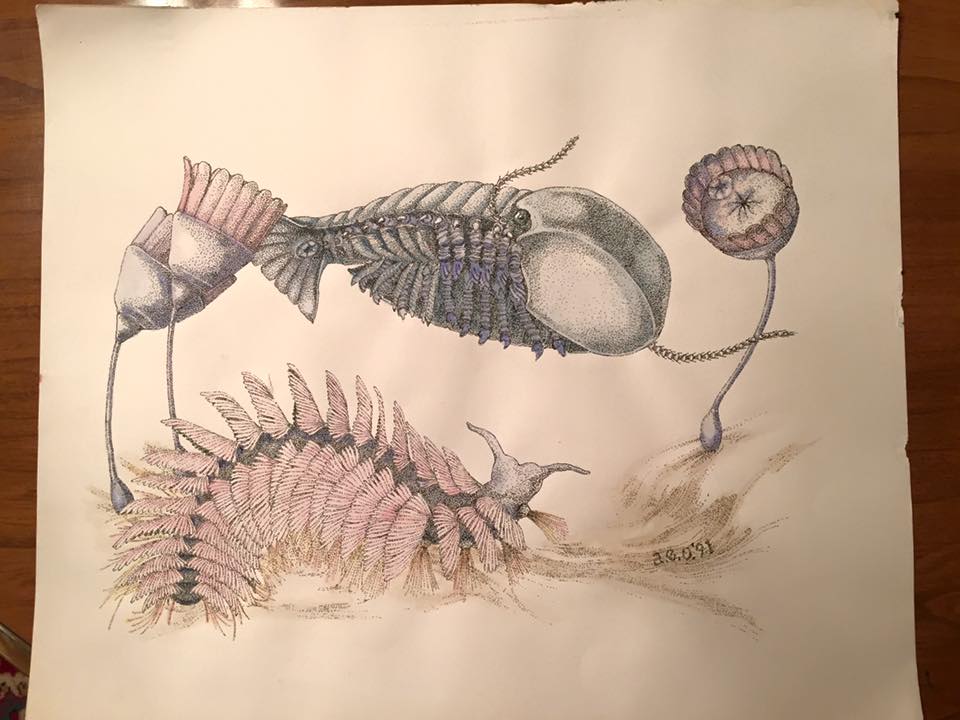

From illustrations in Stephen Jay Gould’s “Wonderful Life;” these creatures were misidentified for decades because of thought-limiting taxonomies. Stippled ink, watercolor.

I have never understood the desire to delete articles in Wikipedia solely on the basis of the highly subjective concept of “notability,” and I’ve fought against deletion of such articles. It’s easy to store the information, and it’s useful to someone or it wouldn’t be there. To these reasons I would add another: the more information you have, the more freedom you have to think flexibly about a subject.

Nicholson Baker supports the concept of a Deletopedia, a wikimorgue where all the “nonnotable” articles removed by the frustrated book-burners on Wikipedia would reside. Baker describes it:

…a bin of broken dreams where all rejects could still be read, as long as they weren’t libelous or otherwise illegal. Like other middens, it would have much to tell us over time.

Why, exactly, is this useful? Because we need taxonomic freedom.

A taxonomy is only as free as its data. The more categories you have—the more data—the more ways a given piece can move from one category to another and be connected—then the more flexibly and creatively you can arrange and understand the data. Not only does the freedom to connect and associate a given piece of data help, but each piece of data increases the number of patterns possible.

How we understand information is driven by the taxonomies—the patterns—we place it in. As Marvin Minsky said, You don’t understand anything until you learn it more than one way. The biologists have known this for some time. Initially biological species classification was based primarily on anatomy and phenotype. But there are many ways to think about organisms: according to evolutionary ancestry (cladistics), according to geography, according to the niche they occupy ecologically, to name a few. What taxonomy you choose to use determines how you’re able to perceive and understand a given organism or system.

The moment you begin to exclude and include along any lines, you begin to enforce a taxonomy of sorts. The taxonomies we use determine and limit the direction and options of our thought. We need to apply them to look at things from a given perspective, but we need to be aware of them so we can change them and see different perspectives. So, thinking in terms of deleting what is not notable is implicitly applying a self-limiting taxonomy. You will not be able to change your perspective to one that makes use of the deleted information, because you will not have the information.

This tendency by some to ignore or remove information that does not fit into their personal taxonomy of relevance is present in library cataloging, too. As a former online cataloger myself, I’m also in support of keeping analog card catalogs as well as digital. Having project-managed teams that converted card catalogs into databases, I’ve seen first-hand how subjective the choices of what pieces of information on the card get migrated onto the database can be. I think every piece of data should be online, but there are plenty of catalogers who skip over descriptive items they find trivial.

Humans are linguistic souls (even the mostly spatial types like myself), and having a new word or symbol attached to a concept immediately adds a tool to our arsenal of thought. This is why one of the first things repressive regimes do is burn the books and suppress the intellectuals. “All the Nazi or Fascist schoolbooks made use of an impoverished vocabulary, and an elementary syntax, in order to limit the instruments for complex and critical reasoning” (Umberto Eco, 22 June 1995, New York Review of Books). We do ourselves a disservice when we close off possible avenues of thought by disregarding data currently not important to us.

Besides, as Flaubert observed, “Anything becomes interesting if you look at it long enough.”

Maybe Wikipedia should make that its motto.

Originally posted on UXtraordinary.com, March 20, 2008.

Like this:

Like Loading...