Cross-posted and expanded from my LinkedIn account.

My grandfather and uncle talking at the German-run camp my uncle was in during World War II.

Everyone demonstrates the fundamental attribution error—a variation of correspondence bias (pdf)—to some extent. We look at the action and assume it’s the character. Even when we know there are extenuating circumstances we do it. The defense lawyer, doing his duty to provide the best defense possible, is seen as supporting crime. The debate student, assigned to defend a certain position, is seen as believing it; no matter the usefulness of the role or the purity of intent, every devil’s advocate runs the risk of being seen as devilish. And of course, the criminally negligent incompetent person driving the car that just cut us off.

In the workplace this can create misunderstandings, usually small but sometimes project-killing or even career-destroying. It’s a problem because the only way to overcome correspondence bias and not commit the fundamental attribution error is to constantly question your assumptions and opinions, looking for the larger context.

Since we’re all story-driven creatures, sometimes an anecdote can help. This is a story of a time a life was on the line, and it’s the best example of correspondence bias I know.

My mother’s uncle was a man named Jara. He was my grandmother’s brother, an artist when he could be (I saw beautiful sculptures and drawings in his widow’s home). His best friend, whose name I don’t know, was a professional artist.

A watercolor portrait of Jara by his best friend, faded but still showing great talent.

During Hitler’s occupation of Prague, Jara and his best friend were sent to a labor camp. At the camp worked another man whose name I don’t know. Let’s call him Karel. Karel worked as an overseer, managing his fellow citizens for the Nazis. Karel was hated. He treated everyone “like a dog,” Jara said, swearing at them and driving them mercilessly, generally making the labor camp experience every bit as awful as you imagine it to be.

Watching Karel’s behavior, day in, day out, Jara and his friend eventually realized Karel could not be allowed to live. It was obvious to them. Karel was a traitor, a collaborator with the enemy, and responsible for much misery. They were young, and passionate about their country. They made a pact together, that if all three of them survived the war, Jara and his friend would hunt down Karel and kill him. They viewed it as an execution.

The war ended, the labor camp closed, and life continued for all three men. Jara and his friend discreetly found out where Karel lived. They obtained a gun, and one day they set out to his home.

Karel lived outside Prague, in a somewhat rural area. When Jara and his friend arrived, Karel’s wife was outside, hanging laundry. When they said they’d known Karel at the labor camp, she smiled and invited them in, calling to Karel that friends from the camp had arrived. They followed her to the kitchen, where they found the monster they sought.

Karel was sitting by the table with a large tub of water and baking soda in front of him, soaking his feet. He was wearing rolled-up pants, suspenders, and a collarless, button shirt, the kind you could put different collars with under a jacket. He greeted them with a broad smile, immediately calling them by name and introducing them to his wife. Jara said Karel was so happy, he had tears in his eyes. He asked his wife to give them coffee, and she brought out pastries, and all sat down to talk about old times.

Jara and his friend were dumbfounded, but did not show it. During the conversation they realized that Karel had not thought of himself as collaborating with the Nazis, but as mitigating their presence. He was stepping in so no one worse could. His harshness was protective; the Germans could not easily accuse the workers of under-producing when Karel pushed his fellow Czechs so hard.

They stayed several hours with Karel and his wife, reminiscing and privately realizing no one was getting shot that day, then took their leave. On the way back they threw the gun into a pond. Jara went on to work at the Barrandov film studios, where he met his wife, Alena (she was an accountant). They married, lived a long life, and were happy more often than not.

Jara and Alena and a canine friend.

Jara was transformed by this experience. Never again would he take any person’s actions as the sum of their character. And I do my best to see things in context and not judge, in part because of the man my great-uncle didn’t kill.

Like this:

Like Loading...

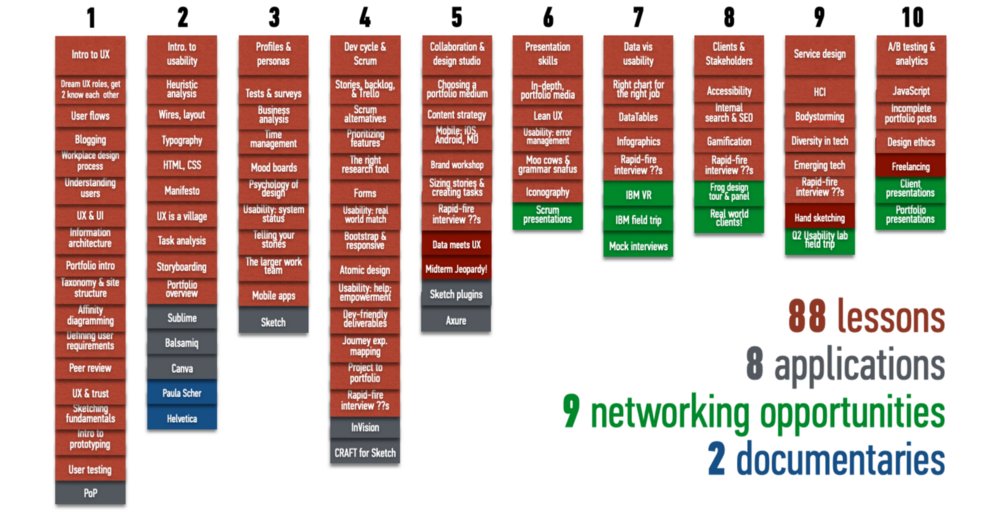

I was thrilled to be able to share my design-focused narrative taxonomy concept and process at the Austin UXPA, hosted by Rackspace. Great crowd, great discussion, great experience. Thanks to organizer (and user research guru) Candice McFarland for organizing this!

I was thrilled to be able to share my design-focused narrative taxonomy concept and process at the Austin UXPA, hosted by Rackspace. Great crowd, great discussion, great experience. Thanks to organizer (and user research guru) Candice McFarland for organizing this!